This is the second in a series of four articles based on my Jupyter Notebooks exploring quantum computing as a tool for generating random number distributions.

The first article showed how a quantum computer could be programmed to generate a uniform random distribution of two bits using operations on qubits. It was a pretty trivial algorithm, and compared with the complexity of generating pseudo-random numbers on a digital computer, showed the advantage of using quantum computers for this application. However, given that I discussed how quantum computers can manipulate probabilities, it’s natural to consider how other, non-uniform, random number distributions might be calculated using a quantum computer. As with the first article, I’m sticking with high-school level maths.

Bell state

A special type of quantum state is known as the Bell state. There are actually four Bell states, but for simplicity, we’ll just pick one. To put a two qubit quantum computer into a Bell state, we will manipulate it to have the state vector

$$\begin{bmatrix}

\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\

0.0 \\

0.0 \\

\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}

\end{bmatrix}$$

which means that a measurement will get either the |00> or |11> outcomes with equal probability, but the |01> and |10> outcomes won’t appear at all. Another way to think of this is flipping two coins, and having them always end up heads-heads or tails-tails, but never getting a heads-tails result.

To get this state vector, it’s not enough to use the H operation, but we need something called the CX operation.

CX operation

The CX operation can be thought of as a “constrained swap” operation which affects pairs of rows in the state vector specified by the states of two qubits (rather than specified by just one qubit, like we saw with the H operation). It will cause the values of those pairs of rows to swap, constrained to those pairs of possible outcomes where the first qubit specified is in the |1> state and that otherwise differ only by the value of the second qubit.

For example, if we start with the usual initial state vector for two qubits:

| Qubits | Initial state vector |

|---|---|

| |00> | 1.0 |

| |01> | 0.0 |

| |10> | 0.0 |

| |11> | 0.0 |

where the |00> outcome has a 100% probability, and now apply the CX operation against the right-most qubit then the left-most qubit, or CX(0,1) to use the Qiskit numbering for qubits, the state vector wouldn’t change at all, since the pair of rows where the right-most qubit is |1> are both the same, i.e. 0.0, so swapping doesn’t change anything.

However, if we firstly use the H operator on rows associated with the right-most qubit, or an H(0) operation, and then perform the same CX(0,1) operation, we get a more interesting result:

| Qubits | Initial state vector | Working out H(0) | Result of H(0) | Working out CX(0,1) | Result of CX(0,1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |00> | 1.0 | =(1.0+0.0)/√2 | 1/√2 | unchanged | 1/√2 |

| |01> | 0.0 | =(1.0-0.0)/√2 | 1/√2 | =0.0 | 0.0 |

| |10> | 0.0 | =(0.0+0.0)/√2 | 0.0 | unchanged | 0.0 |

| |11> | 0.0 | =(0.0-0.0)/√2 | 0.0 | =1/√2 | 1/√2 |

Swapping the rows made a change this time, and we have ended up with the Bell state that we were talking about above.

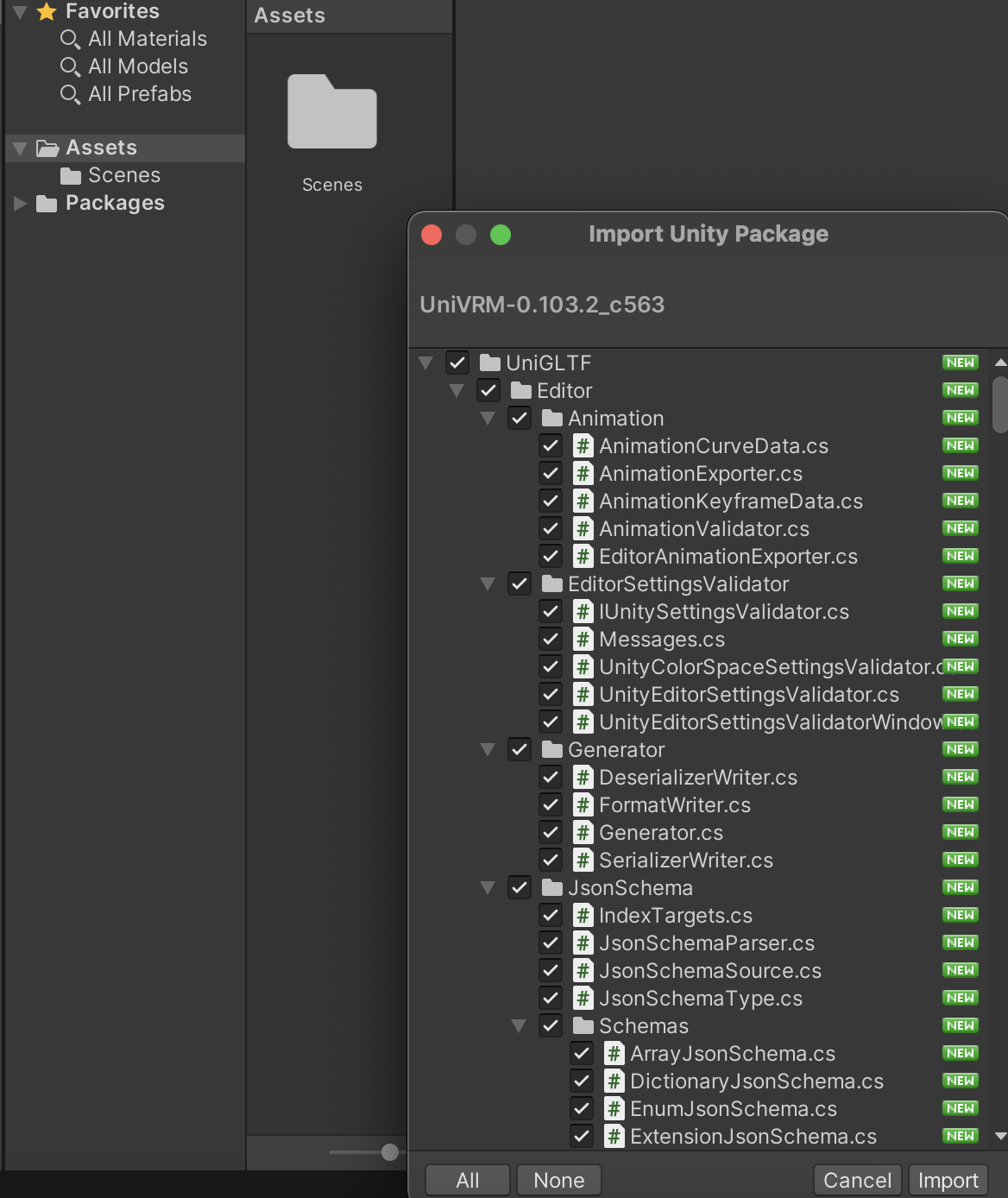

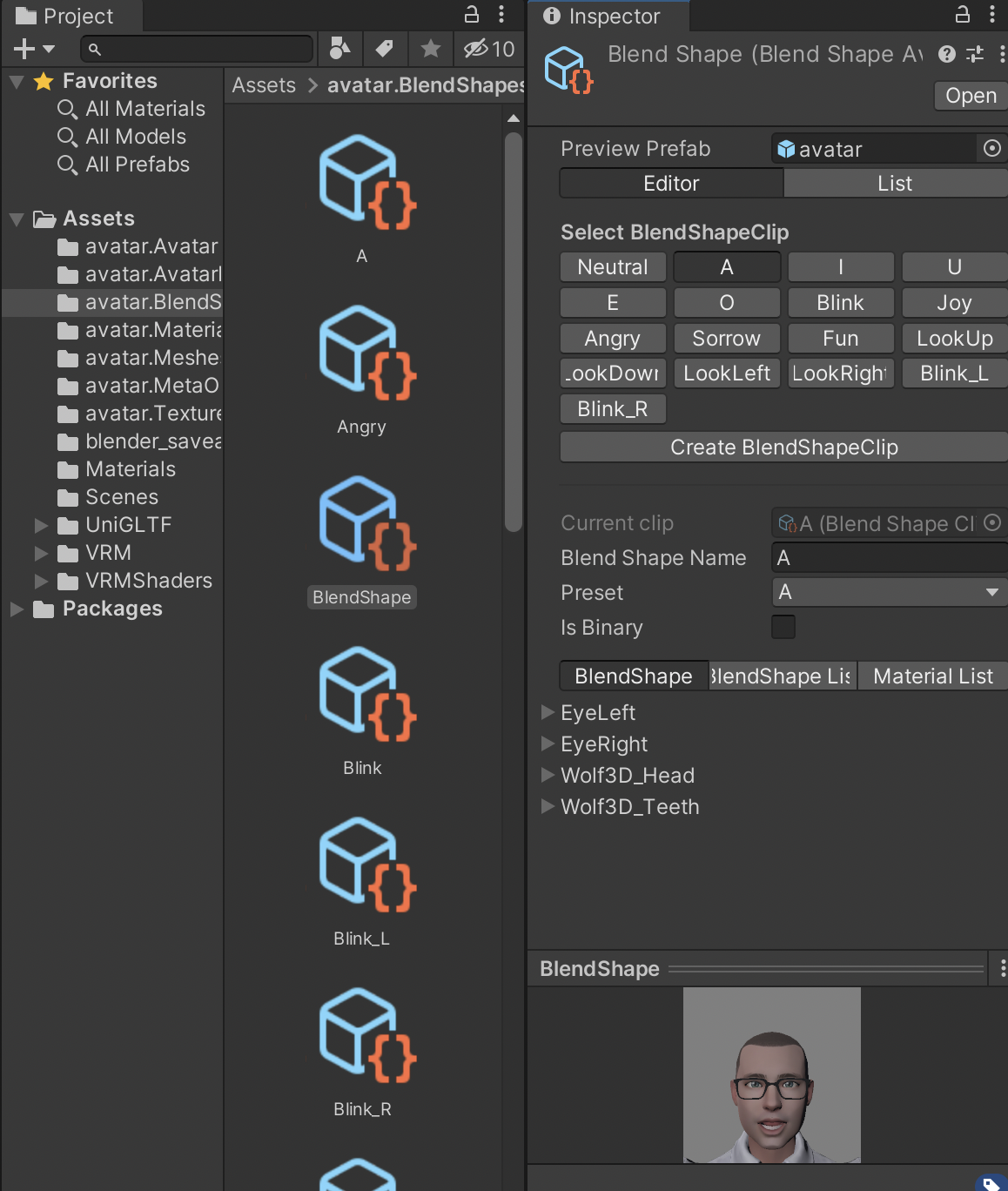

Implementing this on Qiskit

Now, let’s create a histogram of the results we get from performing this on a (simulated) quantum computer, and check that it does what we expect. We’ll use the same approach with Qiskit as we did last time. (You can grab the complete Python script from here, or just type in the code below.)

import numpy as np

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister, execute, BasicAer

from qiskit.visualization import plot_histogram

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

backend = BasicAer.get_backend('qasm_simulator')

q = QuantumRegister(2) # We want to use 2 qubits

algo = QuantumCircuit(q) # Readies us to construct an algorithm to run on the quantum computer

algo.h(0) # Apply H operation on pairs of rows related to qubit 0

algo.cx(0,1) # Apply CX operation, constrained where qubit 0 is |1>

algo.measure_all() # Measure the qubits and get some bits

result = execute(algo, backend, shots=1000).result()

plot_histogram(result.get_counts(algo))

plt.show()

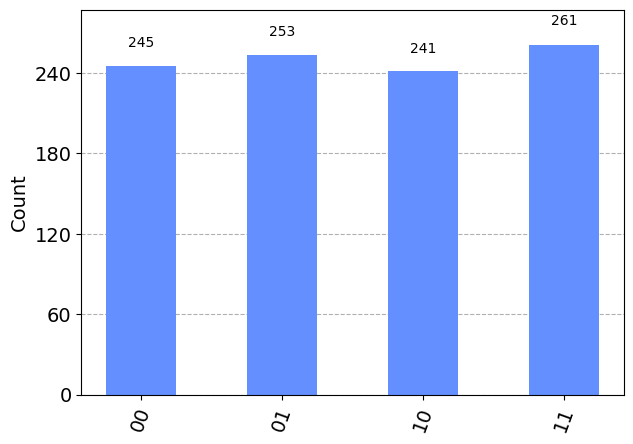

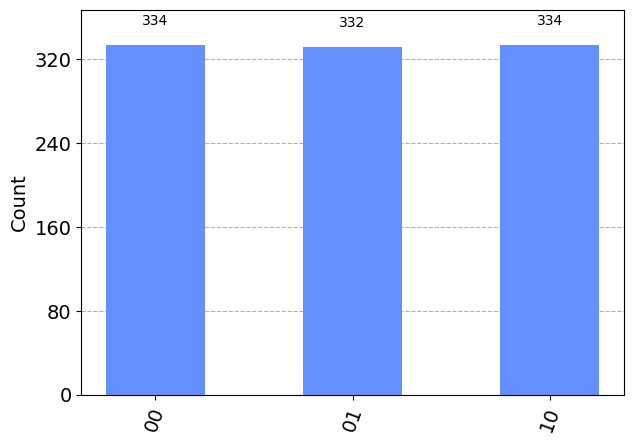

Yes, this is the random distribution we were hoping to get. It is just “00” and “11” with no “01” or “10” results.

RY operation

We’ve achieved a non-uniform distribution, but it’s not a very interesting one. It’s a 50-50 outcome, and we could have achieved that with 1 qubit. We didn’t really need 2 qubits. To create more interesting distributions, we will need another operation. Let’s take a look at the RY operation.

RY adjusts the pairs of state vector rows applying to a specified qubit, and adjusts them by a specified “angle”. If the angle is pi (𝜋), which is an amount in radians equivalent to 180 degrees, the adjustment results in a swap of values and flipping the sign of the first value (we’ll come back to this). But the swap is modified relative to the angle, so we can think of it like a “relative swap” operation.

Let’s have a look at at how it would work on the standard initial state vector, with the specific qubit being the right-most one (or, qubit 0), and for some different angles:

| Qubits | Initial state vector | R(0.0, 0) | R(𝜋, 0) | R(𝜋, 0) again | R(𝜋/2, 0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |00> | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | -1.0 | -1/√2 |

| |01> | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | -1/√2 |

| |10> | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| |11> | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

The first time the RY operation is used, it is given a specified angle of 0.0, and it does absolutely nothing to the state vector. This is correct – with an angle of 0.0, RY will not change anything.

Next, we can see that when the RY(𝜋, 0) operation happens, it swaps the values where the right-most qubit (qubit 0) differ, i.e. the first and second row, and the third and fourth row. In addition, it flips the sign on the first of each pair of rows. The first time RY happens, it simply moves the 100% outcome from |00> to |01>. The second time RY happens, it moves this outcome back to |00> and flips the sign to negative.

What does -100% mean? How can this be a probability? Well, each row of the state vector is a probability amplitude rather than a probability. If a probability amplitude is a real number, i.e. no imaginary component, you can turn it into its corresponding probability by just squaring it. -1.0 x -1.0 is 1.0, so -100% as a probability amplitude is equivalent to a 100% probability. Note that this isn’t just some oddity, but actually part of what makes quantum computers powerful.

The final application of the RY operation in the table is with a specified angle that is 𝜋/2 which corresponds to 90 degrees. It’s mid-way between 0.0 and 𝜋, and produces a result that is also mid-way between the previous results. Where the 0.0 angle didn’t move any of the probability amplitude values between the pairs, and the 𝜋 angle moved all of the probability amplitude values to the alternate row in each pair, the 𝜋/2 angle is halfway between those angles and it moved half the probability amplitude, in the same way the H operator did in the previous notebook.

In fact, we can pick an angle to give to the RY operation that will move a desired fraction of the probability amplitude value between the rows. To swap a fraction “f” of the value from the first row to the second, and bring the opposite fraction (i.e. 1-f) from the second row but with the sign flipped, you use the angle calculated by 2 x arcsin(√f). For our final application of RY above, it had the fraction f=1/2, and it turns out that 2 x arcsin(√(1/2)) = 𝜋/2 which is the angle used in the operation.

We can now use this knowledge to create a range of specific probability distributions for our random bits. The set of operations we have talked about so far – H, CX and RY – should allow us to create any probability distribution. For example, if we want to create a probability distribution where it is equally likely that any of the first three outcomes (|00>, |01>, and |10>) happen and yet the last outcome (|11>) shouldn’t happen, the state vector we’d want to create is:

$$\begin{bmatrix}

\sqrt{\frac{1}{3}} \\

\sqrt{\frac{1}{3}} \\

\sqrt{\frac{1}{3}} \\

0.0

\end{bmatrix}$$

A way to get this is to recognise that if we look at the state vector as two pairs of rows, the first pair of outcomes are twice as likely in total as the second pair of outcomes. We can use the RY operation to swap (the square root) of a third of the overall probability to the second pair. We can then use a sequence of H, RY, CX and RY operations to spread the probabilities within each pair. This looks like:

| Qubits | Initial state vector | RY(2 x arcsin(√(1/3)), 1) | H(0) | RY(𝜋/4, 0) | CX(1, 0) | RY(-𝜋/4, 0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |00> | 1.0 | √(2/3) | √(1/3) | 0.3125 | 0.3125 | √(1/3) |

| |01> | 0.0 | 0.0 | √(1/3) | 0.7543 | 0.7543 | √(1/3) |

| |10> | 0.0 | √(1/3) | √(1/6) | 0.2209 | 0.5334 | √(1/3) |

| |11> | 0.0 | 0.0 | √(1/6) | 0.5334 | 0.2209 | 0.0 |

You can see here that after the H(0) operation, the first two rows have the values we want, but the final two rows had the desired values before the H(0). The operations following the H(0) have the effect of undoing the H(0) operation on the final two rows but leaving the first two rows alone. Note that the final two RY operations are opposite signs to each other, so they should cancel each other out, but a CX(1,0) operation has been done in the middle. This CX operation, in swapping the final two rows, has the effect of making it as if the first of the final two RY operations was also a negative angle for those rows, so instead of cancelling out (like happened on the first two rows), the two RY operations on those rows add together as if it was an RY operation of -𝜋/2. As we saw above, an RY operation with the angle 𝜋/2 is similar to an H operation, and with the negative angle, the RY operation acts to reverse the H.

Don’t worry if you didn’t fully follow that. This sort of procedure is called “amplitude embedding” or “state preparation”, and there are various algorithms to do this, many of which get quite esoteric. The above procedure was inspired by a paper by Mottonen, Vartiainen, Bergholm, and Salomaa. The main thing to note is that quantum computers allow arbitrary non-uniform distributions to be constructed.

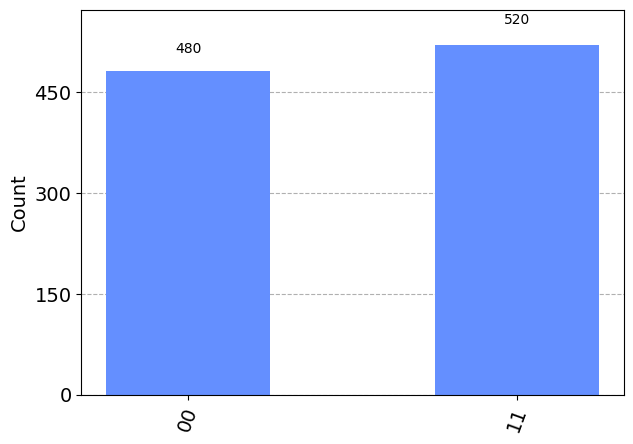

Implementing this on Qiskit

Let’s test the above procedure and see if it does what we expect. (You can grab the complete Python script from here, or just type in the code below.)

import numpy as np

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister, execute, BasicAer

from qiskit.visualization import plot_histogram

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

backend = BasicAer.get_backend('qasm_simulator')

q = QuantumRegister(2) # We want to use 2 qubits

angle1 = 2 * np.arcsin(np.sqrt(1.0/3.0))

angle2 = np.pi / 4

algo = QuantumCircuit(q) # Readies us to construct an algorithm to run on the quantum computer

algo.ry(angle1, 1) # Apply RY operation to swap 1/3 of qubit 1's value

algo.h(0) # Apply H operation on pairs of rows related to qubit 0

algo.ry(angle2, 0) # Apply RY operation to perform a half of H on qubit 0

algo.cx(1,0) # Apply CX operation, constrained to where qubit 1=|1>

algo.ry(-angle2, 0) # Apply RY operation to undoing half of H on qubit 0

algo.measure_all() # Measure the qubits and get some bits

result = execute(algo, backend, shots=1000).result()

plot_histogram(result.get_counts(algo))

plt.show()

This is exactly what we were hoping to see. It is “00”, “01” and “10” split three ways, and with no “11” results.

In conclusion

We have added two more operations to our set, and seen how to use them on a quantum computer to create a variety of random distributions, such as the Bell state:

| Operation | Short-hand description | Specified by | Detailed description |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | “half” | 1 qubit | For all pairs of rows that differ only by the value of a specific qubit in the outcome, replace the first row value with a new value that is the sum of the original values divided by √2, and the second row value with the difference between the original values divided by √2. |

| CX | “constrained swap” | 2 qubits | For all pairs of rows where the first qubit specified is in the |1> state in the outcome, and where otherwise the rows differ only by the value of the second qubit specified, swap the rows in the pair. |

| RY | “relative swap” | 1 angle and 1 qubit | For all pairs of rows that differ only by the value of a specific qubit in the outcome, swap a fraction “f” of the value from the first row to the second, and bring the opposite fraction (i.e. 1-f) from the second row but with the sign flipped, where “f” is specified as the angle 2 x arcsin(√f). If “f” is 1.0, the angle will be 𝜋. |

The next article will look at how to implement digital computing functions through operations on the state vector.