This post focuses on one of the points covered in the Far Phase board training session on Generative AI, and complements the previous posts on AI risks concerning hallucinations (making mistakes) and intellectual property.

There seems to be a new AI tool every week, and that every month a big AI firm is announcing new features. It isn’t surprising that I am hearing decision-makers are worried about making a bet on AI that is quickly obsoleted.

For organisations that have previously created Data & AI Governance boards / risk committees / ethics panels, there may also be a worry that such governance processes are asking for a level of evidence about new AI opportunities that is time-consuming to gather and create a barrier to progress. Perhaps this results in leaders who fear that their organisation is falling behind similar organisations who are announcing big deals and making bold moves.

How to chart a way forward?

Pace of Change

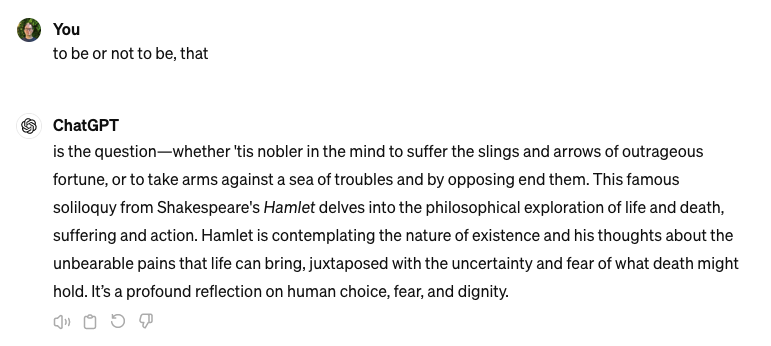

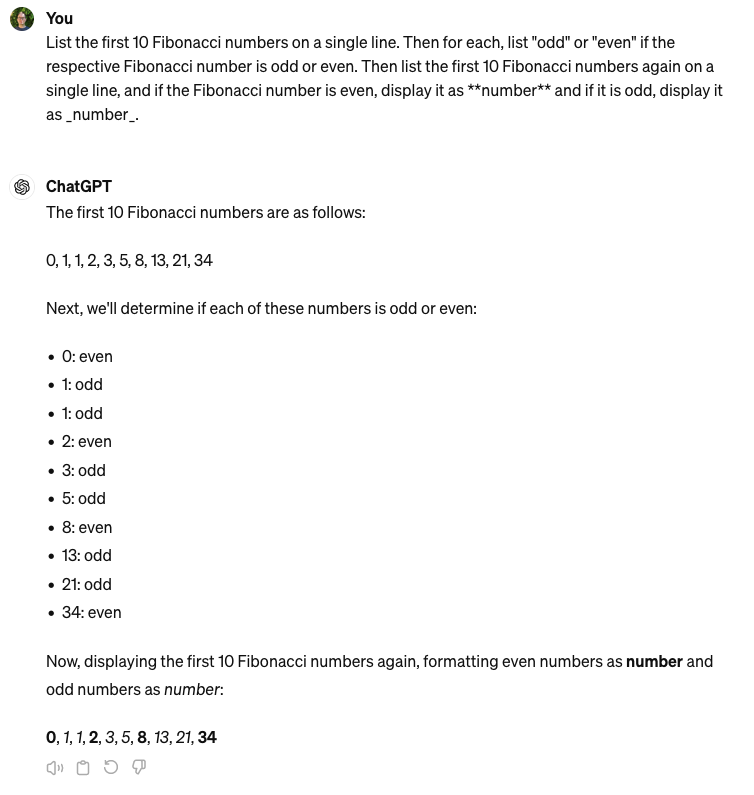

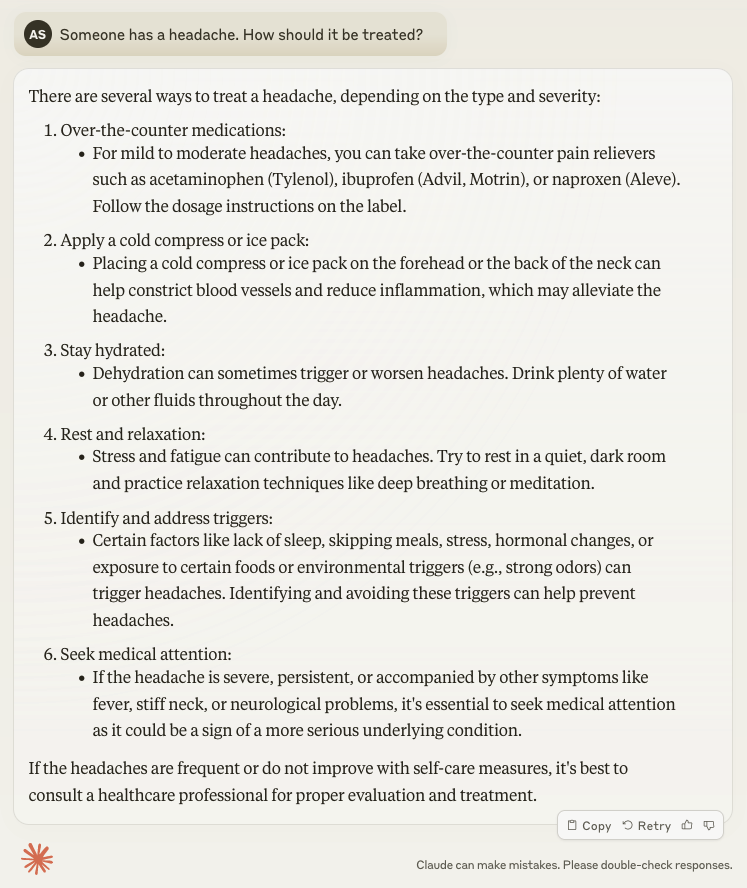

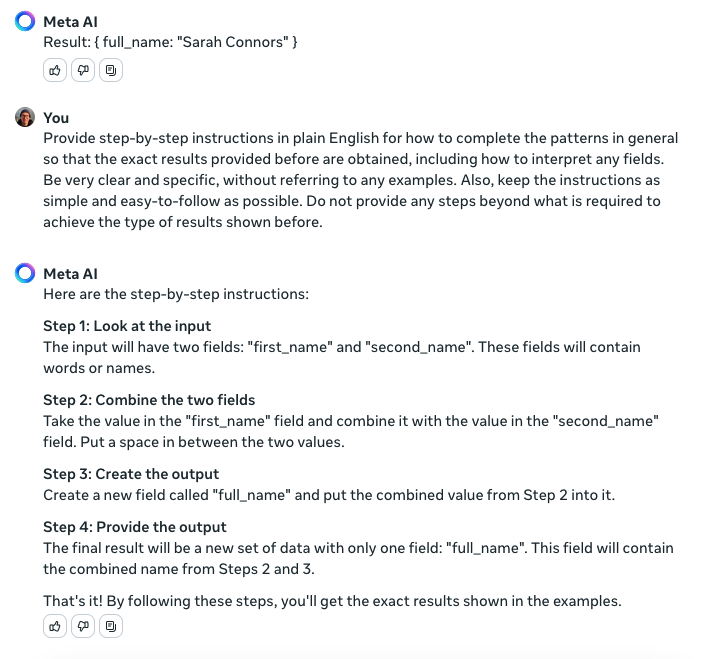

It is rare that a technology category moves as quickly as Generative AI (GenAI) is moving, as shown by the following two charts.

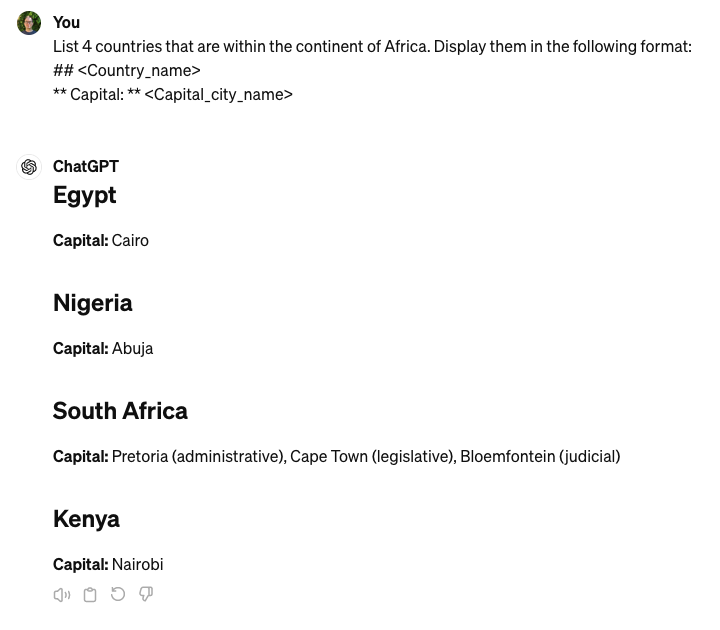

OpenAI’s ChatGPT itself is one of the most quickly adopted online services ever. It reportedly had 100 million users within two months of launching at the end of November 2022. While it wasn’t the first publicly available GenAI service, as image and software development tools using GenAI technology had been released previously, its speed of adoption shows how quickly tools in this category can become mainstream.

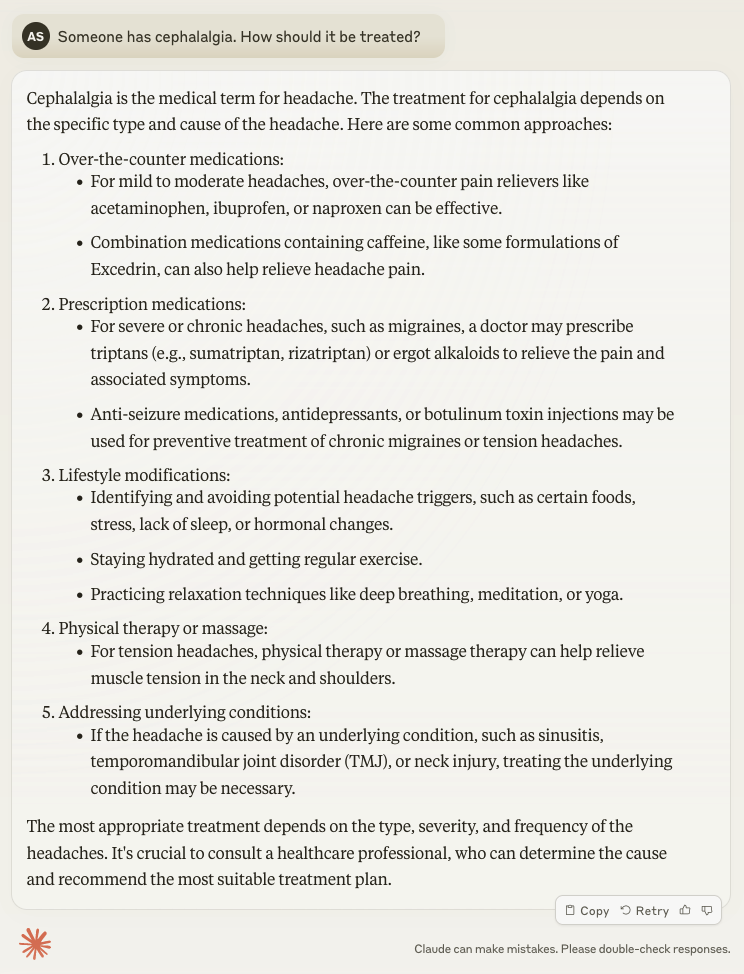

The above graph from the Stanford AI Index 2025 report shows the rate of improvement of select AI benchmarks as they progress towards or exceed average human performance, over the course of the past 13 years. As you get closer to the present day, you can see the rate of improvement getting faster (lines with steeper slopes), at the same time tougher problems are being tackled by AI. For instance, the steep black line that appears from 2023 and exceeds average human performance after just a year is for a benchmark relating to correctly answering PhD-level science questions.

The speed of adoption and speed of technology improvement is also reflected in the way that AI firms release major new AI models and tools on a frequent basis. This trend is clear when looking at the various releases of ChatGPT, as a proxy for the speed of the whole industry. It is typical for a model to be replaced with something significantly better within six months, and the speed of change has not been slowing down.

| 6 month time period | ChatGPT releases | Count of releases |

|---|---|---|

| 2H2022 | Original ChatGPT (GPT-3.5) | 1 |

| 1H2023 | GPT-4 | 1 |

| 2H2023 | 0 | |

| 1H2024 | GPT-4o | 1 |

| 2H2024 | GPT-4o mini, o1-preview, o1-mini, o1, o1-pro | 5 |

| 1H2025 | o3-mini, o3-mini-high, GPT-4.5, GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1 mini, o3, o4-mini, o4-mini-high, o3-pro | 9 |

Keeping up

This pace of change is a universal challenge. Academics in the AI domain are publishing articles about AI technology that is out of date by the time the article is published. (Similarly, this post is quite likely to be out of date in six months!) Businesses also struggle to know whether to jump on the latest AI technology or hold out a few months for something better.

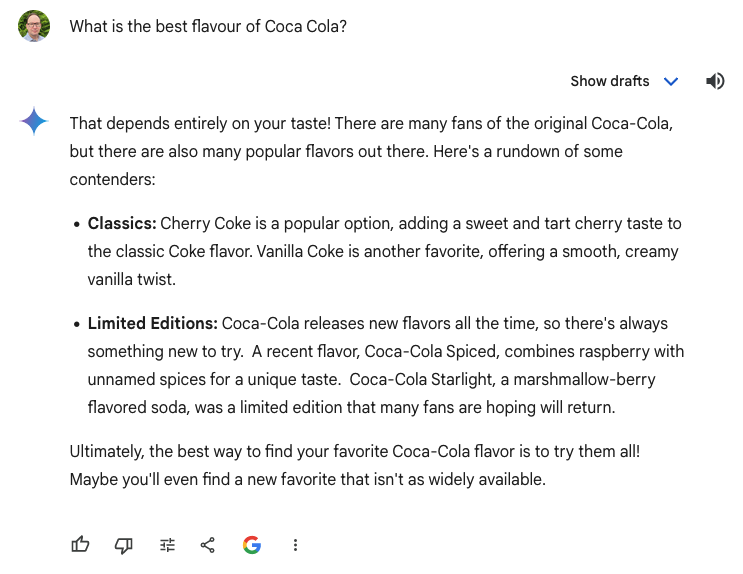

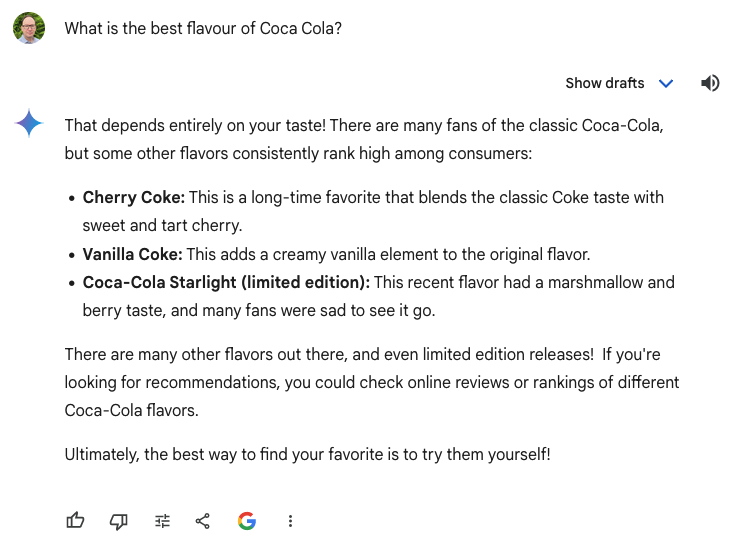

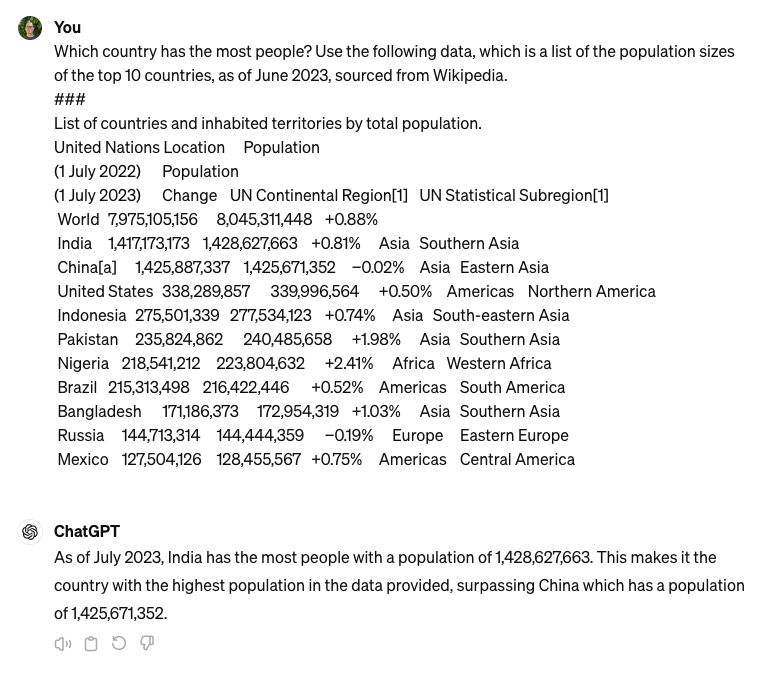

As a specific example, in May 2024, ASIC (Australian Security & Investments Commission) shared a report about their own trial of using GenAI technology. The report was dated March 2024, and referred to a 5 week trial that ran over January and February that year, where AWS experts worked with ASIC to use GenAI to summarise some public submissions, and learn how the quality compared with people doing the same work. The conclusion was that GenAI wasn’t as good as people, based on using Meta’s Llama2 model. However, Llama2 was already obsolete by the time the report was shared, as Llama3 had been launched in April 2024.

The frankly ridiculous speed of change in this technology area poses a challenge for IT/technology governance. The traditional approach to procuring technology used by large firms is a RFI/RFT process, spending 12-18 months implementing and integrating it, and spending millions of dollars . This results in wasted money when the technology is obsolete before the ink on the requirements document is dry. How do executive leaders and board directors ensure this doesn’t happen at their organisations?

At some point (perhaps in a few years), things will likely slow down, but organisations that choose to wait for this are also choosing to forgo the benefits of GenAI in the meantime and may be paying a significant opportunity cost. There is currently a bunch of FOMO-driven marketing from AI firms that play on this, and Gartner’s hype cycle shows many GenAI technologies are clustered around the “peak of inflated expectations”. While it is fair to say that organisations should avoid doing *nothing*, that’s different to saying they should be adopting everything.

Effective governance

The use of a Data & AI Governance board or AI & Data Risk group to govern GenAI is not going to help with this problem. Instead, the smart play is to use governance to drive the organisation to learn at a speed close to the speed of change. Specifically, use governance around an innovation framework to identify/prove GenAI opportunities and to centralise the learnings.

An innovation framework in this context is a clear policy statement that outlines guardrails for ad-hoc experimentation with GenAI tools. It clarifies things like the acceptable cost and duration for an experiment, what types of personal/confidential data (if any) can be used with which types of tools, what the approval/registration process is for this, and how the activity and learnings from it will be tracked.

Such a framework allows people across the organisation to test out GenAI tools that can make their work life better, and build up organisational knowledge. Just as there is no single supplier for all IT applications and systems used by an organisation, e.g. across finance, HR, logistics, CRM, collaboration, devices, etc., it is unlikely that there will be a single supplier for all GenAI tools. While there is a level of risk in giving people latitude to work with tools that haven’t gone through rigorous screening processes, the innovation framework should ensure that any such risk is proportionate to the value derived from learning about the best of breed GenAI tools available in key business areas.

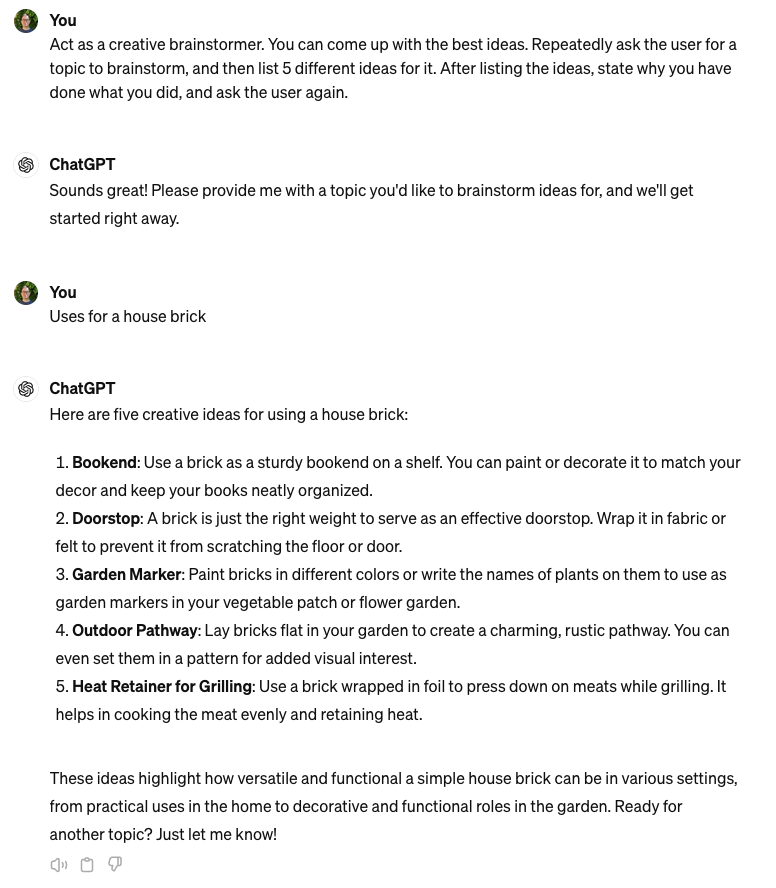

Without a way for people in an organisation to officially use GenAI tools to help with their jobs, a risk is that they will use such tools unofficially. The IT industry is well aware of “shadow IT”, where teams within an organisation use cloud services paid on a credit card, independent of IT procurement or controls. With many GenAI tools being offered for free, the problem of “shadow AI” is particularly widespread. A recent global survey by Melbourne Business School found that 70% of employees are using free, public AI tools, yet 66% used AI tools without knowing if it was allowed, and 44% used AI tools while aware that it was against organisational policies. With GenAI tools easily accessible from personal devices, it is difficult to eliminate it through simply blocking it on work devices.

Organisations that are looking to take advantage of GenAI tools will typically have a GenAI policy and training program. (Note that generic AI literacy programs are not sufficient for GenAI training, and specialised GenAI training should cover topics like prompt-writing, dealing with hallucinations, and GenAI-specific legal risks.) An innovation framework can be incorporated into a GenAI policy and related training rather than being a general framework for innovation and experiments. However, more organisations should be putting in place AI policies, as a recent Gallup survey of US-based employees found that only 30% worked at places with a formal AI policy.

As well as the ASIC example above, many organisations are running quick GenAI experiments. Reported in MIT Sloan Management Review, Colgate-Palmolive has enabled their organisation to do a wide range of GenAI experiments safely. They have curated a set of GenAI tools from both OpenAI and Google in an “AI Hub” that is set up not to leak confidential data, and provided access to employees once they complete a GenAI training module. Surveys are used to measure how the tools create business value, with thousands of employees reporting increases in quality and creativity of their work.

Another example is Thoughtworks, who shared the results of a structured, low cost GenAI experiment run over 10 weeks to test whether GitHub Copilot could help their software development teams. While they found an overall productivity improvement in their case of 15%, more importantly they built up knowledge on where Copilot was helpful and where it was not, and how it could integrate into the wider developer workflows. By sharing what they learned, the rest of the organisation benefits.

Recommendations

Board directors and executive leaders might ask:

- How are both the risks of GenAI technology obsolescence and being slow to adopt best-of-breed GenAI tools captured within the organisation’s risk management framework?

- How is the organisation planning to minimise the use of “shadow AI” and the risks from employees using GenAI tools on personal devices for work purposes?

- Does the organisation have an agreed innovation framework or AI policy that enables GenAI tool experiments while accepting an appropriate amount of risk?

In conclusion

Generative AI tools are improving a rate of change and with broad impact that is unique. It is common for a tool to be overtaken by one with significantly better performance within six months. Traditional RFI/RFT processes are not intended to support an organisation making implementation decisions about new tools this quickly. In addition, shadow AI poses risks to an organisation if it does not offer its people GenAI tools that are comparable with best of breed options.

To tackle this, organisations should ensure that they are building up organisational knowledge at the same rate GenAI tools are evolving. This way, when clear business value from a new tool (or a tool upgrade) is identified, it can be rolled-out to all relevant parts of the organisation. Putting in place an innovation framework, possibly as part of an AI Policy, will help ensure experiments can be carried out safely and at low cost by the people who would like to use the latest GenAI tools.

Board directors and senior leaders should ensure that their organisation is properly considering the risks of these issues and has a plan to address them.