I read my first proper e-book 17 years ago. It was 1994, and I enthusiastically devoured Bruce Sterling‘s (free!) digital release of The Hacker Crackdown, scrolling through it line-by-line on a small CRT display. At the modem speeds of the day, it took around 7 mins to download it, and it must’ve taken me a week to read it.

I read my first proper e-book 17 years ago. It was 1994, and I enthusiastically devoured Bruce Sterling‘s (free!) digital release of The Hacker Crackdown, scrolling through it line-by-line on a small CRT display. At the modem speeds of the day, it took around 7 mins to download it, and it must’ve taken me a week to read it.

While it was common to write long form content – books, essays, dissertations, and the like – on computers, it is interesting how uncommon it was (for anyone but the author) to read such content on computers. Essentially, computers were a write-only medium when it came to books.

At the time, I knew it was a bit strange to read a whole book this way, but it was a great experience. The book was about the computer culture of the time, and so it was appropriate to be reading it hunched over a computer. However, the process of discovering that a book exists, getting it, and then beginning to read it – all within half an hour – was very satisfying.

Given how long ago I started to read e-books, I’m a little late to the party regarding the modern generation of them. This has now been rectified.

I had to buy our book-club book as an e-book through the Kindle app on our iPad. Not only was it available in time for us to read it compared with buying it for real or borrowing it from the library (it took much less than 7 minutes to download), but it was also:

- cheaper (less than half the price),

- easier to share between Kate and myself (no risk of losing multiple book-marks),

- easier to read in bed (self-illuminating, so less distracting to the other person), and

- took up none of the scarce space on our bookshelves (given that the book turned out to be not-very-good).

And with the latest book-club book, Bill Bryson’s At Home, I found myself wishing it was an e-book rather than hard-cover. While it would’ve been a lot lighter (the iPad 2 is 600g versus the book at 900g), it was more that this book mentions all sorts of interesting things in passing that made me want to look into them in more detail before continuing. It would’ve been much more convenient to jump straight to a web browser as I read about them, rather than having to put the book down and find an Internet-connected device in order to indulge my curiosity.

All the various advantages that e-readers and tablets have over their physical book counterparts remind me of the advantages that digital music players had over CDs, cassettes and records. However, as I’ve written about before, the digital music player succeeded when it was able to offer the proposition of carrying all one’s music, but e-readers cannot yet offer this.

Apple’s iPod, supported three sources for acquiring music: (i) importing music from my CDs, (ii) file sharing networks (essentially, everyone else’s CDs), and (iii) purchase of new music from an online shop (iTunes Music Store). For e-books on my iPad, it’s not easy to access anything like the first two sources, while there are at several online shops able to provide new reading material. As a result, the iPad (or any other e-reader) doesn’t really offer any way for me to take my book library with me wherever I go.

Although, that would be pretty amazing, it’s honestly not that compelling. I could go back and re-read any book whenever I want, but that’s not actually something I feel I’m missing. I could search across all my non-fiction books whenever I needed to look something up, but really I just use the Internet for that sort of thing.

The conclusion may be that books aren’t enough like music. The experience of consuming music – whether old media or new digital – is sufficiently similar that the way for technology to offer something more is to, literally, provide more of it – thousands of pieces of music. However, for books, the new digital experience of books may end up being a very different thing to the books of old.

Already, there are books with illustrations that obey gravity and can be interacted with, books that are like a hybrid of a documentary and allow you to dig deep as you like into the detail, and we’ve only just started. If these are the sort of books that I’m going to have on my iPad in future, why would I want to be putting my old-school book collection on there instead? I can also imagine publishers seeing the chance to get people to re-purchase favourite books, done with all the extras for tablets, in the same way that people re-purchased their VHS collection when they got a DVD player.

So, while my book-club e-book experience wasn’t materially different to the one I had 17 years ago, we are going through a re-imagining of the digital book itself. If it took journalists 40 years from the first email in 1971 to officially decide to drop the hyphen from “e-mail”, then the fact that we still commonly have a hyphen in “e-book” suggests it’s not a mature concept yet, despite the progress of a mere 17 years.

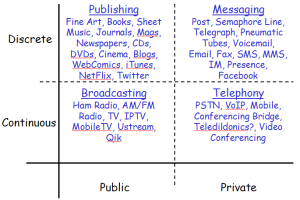

One of the first observations is that all of these examples of communications require some sort of network. The different quadrants have different types of networks, clearly. I’m interested in seeing if there are some common characteristics shared by the examples in the e.g. public or discrete categories.

One of the first observations is that all of these examples of communications require some sort of network. The different quadrants have different types of networks, clearly. I’m interested in seeing if there are some common characteristics shared by the examples in the e.g. public or discrete categories.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=57ef8ddb-39b0-417f-9c8a-b4593a666d27)