Last month, Apple released their latest device – the iPad. It is capable of many wonderous things, and has many fabulous properties, but of all of them, for now I am interested in just three: its screen, its weight, and its ability to show video.

Last month, Apple released their latest device – the iPad. It is capable of many wonderous things, and has many fabulous properties, but of all of them, for now I am interested in just three: its screen, its weight, and its ability to show video.

As various other manufacturers rush to market with devices to compete in the segment that Apple has just legitimised, they will most likely produce things that share those same three properties. However, as it is still early days, we don’t yet know for sure what people will end up doing with these devices. That’s why it’s so much fun to speculate!

The iPad has a 24cm (diagonal) screen, weighs about 700g (WiFi version) and can deliver TV quality video from the Internet to practically wherever in the house you decide to sit yourself down with it. If you hold it up in front of your face (about 60cm away), it’s as big as if you were watching a 120cm (diagonal) TV from 3m away. And, while lighter than a 120cm TV, it’s going to feel heavy pretty quick.

However, 700g is not very heavy if you’re willing to rest it on your lap, and there’s another category of content consumption “device” that is comparable in this regard: the book. I am willing to spend hours intently focused on a book while reading it, and a quick weigh of some of my books (using the handy kitchen scales) suggests the iPad is not unusual…

- Douglas R Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher Bach (paperback) – 1.1kg

- Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor (paperback) – 500g

- Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon (hardcover) – 1.4kg

- J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (hardcover) – 800g

Which provides some legitimisation of a “TV-watching” scenario of a family in their lounge room, with everyone watching a show on their tablet device. (Assuming that you have overcome issues like individuals’ TV audio interfering with others and ensuring adequate bandwidth for everyone.) However, this scenario feels strange, even anti-social.

I am perhaps conditioned by the ritual of people coming together to share a TV watching experience. And before we had TVs, people came together to share a radio listening experience. But before broadcasting technologies, what did we do? In reality, this sort of broadcasting experience is a relatively recent phenomenon. Before that, presumably we all sat around in the lounge room and read books.

I’ve previously written on the idea that people prefer the personal, and that a personal TV experience will be preferred to a shared TV experience. The iPad and similar devices have the potential to enable this, through becoming as light and portable as books.

“Netbooks” also have similar attributes to the iPad. However, they tend to weigh at least 1 kg and have screens that are smaller. So, while future Netbooks might have the right form factor, it certainly isn’t common yet. The iPad is the first mass-market device that properly fills this niche.

The issue of the scenario feeling anti-social is still a little troubling. While our ancestors might have looked up over their books and engaged in a casual chat, momentarily pausing their reading, this is harder to accomplish with a video experience. Not only are the eyes and ears otherwise engaged, making casual interruption more difficult, but the act of pausing and resuming is not as easy either.

I suspect that while we’re now reaching the point where hardware can fill the personal TV niche, the software is not yet ready. We may need eye-tracking software that pauses the video when the viewer looks away, integration of text-based messaging alongside video-watching, and other adaptations to the traditional video player software.

I’m keen to see what competition in this new segment produces.

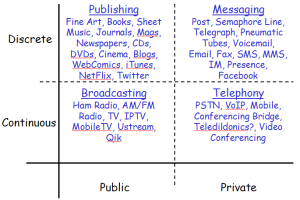

One of the first observations is that all of these examples of communications require some sort of network. The different quadrants have different types of networks, clearly. I’m interested in seeing if there are some common characteristics shared by the examples in the e.g. public or discrete categories.

One of the first observations is that all of these examples of communications require some sort of network. The different quadrants have different types of networks, clearly. I’m interested in seeing if there are some common characteristics shared by the examples in the e.g. public or discrete categories.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=57ef8ddb-39b0-417f-9c8a-b4593a666d27)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=9912f7b3-496c-48dd-939b-048bdb8aafd8)