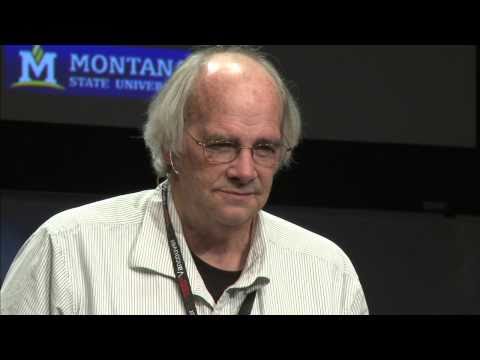

This is something that blew my mind last week. Some paleontologists are convinced that there were fewer dinosaurs than we thought – that some different types of dinosaurs were just the adult form of another one, despite the fact that they look completely different. It’s explained in this 20 minute TEDx talk:

To completely spoil the video, Jack Horner (the paleontologist inspiration behind Jurassic Park) believes that:

- the Dracorex, Stygimoloch and Pachycephalosaurus were the same dinosaur

- the Triceratops, Nedoceratops and Torosaurus were the same dinosaur

- the Edmontosaurus and Anatotitan were the same dinosaur

- the Nanotyrannus and Tyranosaurus were the same dinosaur

and he deduces this through cutting open dinosaur skulls and bones at the Museum of the Rockies where he is the curator. Those skulls/bones of the suspected “younger” dinosaurs are spongy while the “older” ones are more solid. If other museums were happy for scientists to cut open their dinosaurs perhaps this would’ve been discovered sooner.

But perhaps there’s another angle. If women were more involved in the science of paleontology earlier on, perhaps this would’ve been discovered sooner.

Part of the basis for the theory is that no child dinosaurs (ie. small / less-developed specimens) of the now-suspected “older” dinosaurs have been found to date. To my admittedly non-expert mind, this is pretty damning evidence right there. According to Wikipedia, the Torosaur (for example), was first discovered in 1891. Somehow, it has taken over a hundred years for a dinosaur expert to come up with evidence to support the simple theory that the reason there are no child versions found in all this time is that there are no child versions, ie. that it is an adult version.

Horner himself puts forward the explanation that scientists just like to name things – the more dinosaurs, the more chance for names. However, attempting to put on a feminist-shaped hat, I would also think that an alternative explanation is that the predominantly male dinosaur collectors of the early years of paleontology were not interested in looking for child dinosaurs – the only interesting dinosaurs were the big ones, that probably also turned out to be the male ones. I wouldn’t blame the individual collectors for this – I would think it likely that this was the culture of the industry at the time. Hence, it’s only as the industry changed, and more women came into it for example, that such thinking changed – thinking that enabled a real interest in finding child dinosaurs and explaining what happened to them. (And I realise that I’m falling for a stereotype here that women would be more interested in dinosaur children than men would be, but I suspect it’s true all the same.)

This is merely a hypothesis, and informed merely by personal speculation and a few web searches today. For example, an article from 2010 in Wired trying to identify significant female paleontologists in the face of a complete lack of their public presence. Also, a blog post from a female paleontologist describing how it has traditionally been a male-dominated profession (the photos of Paleontologist Barbie are worth a look, too). In any case, I wonder if there will be further breakthroughs due to the changing gender mix in science.